Keynote speakers

Libora Oates-Indruchová

Libora Oates-Indruchová is cultural scientist, literary scholar, English scholar and professor of gender sociology from the University of Graz, who is also a member of the scientific board of the Institute for the study of totalitarian regimes. Her research interests include gender issues in socialism and post-socialism, censorship in the former Eastern Bloc and narrative research. She did her postgraduate studies at Lancaster University and her habilitation at the University of Szeged. She is the author of Discourses of Gender in Pre- and Post-1989 Czech Republic, editor of two anthologies of Anglo-American feminist thought, and co-editor of The Politics of Gender Culture under State Socialism: an Expropriated Voice. She is the social science officer of the Scientific Council of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

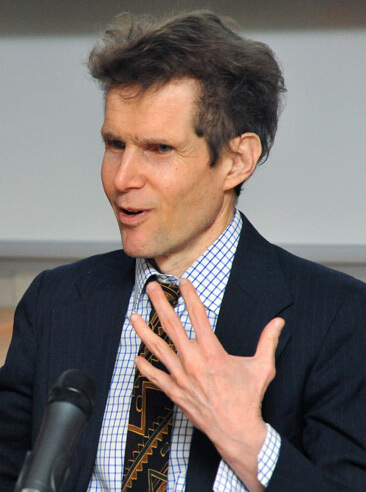

Mark Kramer

Mark Kramer is Director of Cold War Studies at Harvard University, a Senior Fellow of Harvard’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, and Director of Harvard’s Sakharov Program on Human Rights. Originally trained in mathematics at Stanford University, he went on to study International Relations as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University and an Academy Scholar at Harvard’s Academy of International Studies. In addition to his appointments at Harvard, he has been a visiting professor at Yale University, Brown University, Aarhus University in Denmark, and American University in Bulgaria. He has published numerous books and many articles and has long been the editor of the Journal of Cold War Studies, a quarterly academic journal published by MIT Press, and editor of the Harvard Cold War Studies Book Series.

Tim Haughton

Tim Haughton is Associate Professor of European Politics at the University of Birmingham, where he served as Head of the Department of Political Science and International Studies (2016–2018). He has held Visiting Fellowships at Harvard University’s Center for European Studies and the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, and he was an Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation Fellow at Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies. Dr Haughton has good links with the policymaking community, having briefed inter alia five British Ambassadors to Slovakia before they took up their posts. His research interests encompass electoral and party politics, electoral campaigning, and the domestic politics of Slovakia, Slovenia and the Czech Republic. He is the co-author with Kevin Deegan-Krause of The New Party Challenge: Changing Cycles of Party Birth and Death in Central Europe and Beyond (Oxford University Press, 2020), the author of Constraints and Opportunities of Leadership in Post-Communist Europe (Ashgate 2005), the editor of Party Politics in Central and Eastern Europe: Does EU Membership Matter? (Routledge, 2011) and served as the co-editor of the Journal of Common Market Studies’ Annual Review of the European Union for nine years (2008-16).